VOL. 1 -- NO. 2CALGARY, ALBERTA, CANADAThursday, November 21, 2024 | ||

Opinions / EditorialsCONTENTS

What's Inside (click any page number)

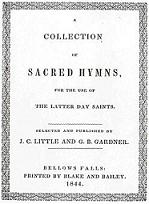

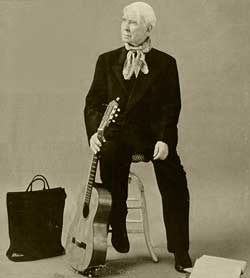

Old Hymns NotAs Popular:Left out of New HymnalsW. Johnson, Editor In our newly designed churches, with lots of light, plenty of air-conditioning in summer, and lots of heat in winter, there are some new hymns being sung. They aren't the old time hymns that I remember when I was a kid: “Rock of Ages”, “Amazing Grace”, “The Mercy Seat”. The hymns these days, beautiful as they are, are modern hymns, and they reflect the changes that have come with the various modifications to the rites and rituals of the different denominations: Anglican, Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, and so forth. These hymns, for the most part, were written in the 1980s and 1990s. Personally, I prefer the songs from the 1880s and 1890s: “O God Almighty Father”, “Just As I Am”, “Father Hear Thy Children's Call’, to name a few. It was while listening to a hymn arranged for guitar by John Fahey (“In Christ There Is No East or West”) that I first realized how incredibly beautiful the music can be in the old hymns, not to mention the lyrics. In Fahey's arrangement, for example, there is a chord progression that goes from G major to D major to C major. Fahey changes the D major chord to a D minor, which adds an incredible change of mood to the piece. He makes a further change from an F major to an F7th, which echoes the mood created by the D minor chord. I began researching other hymns that could be changed in such a manner and soon discovered that artists such as Mississippi John Hurt and the Reverend Gary Davis sprinkled their original compositions with chord progressions and changes that they discovered in many old hymns, modifying traditional arrangements the way Fahey did, and altering the chord progressions in some cases. The Feet of Judas

CHRIST washed the feet of Judas!

Christ washed the feet of Judas!

Christ washed the feet of Judas!

Christ washed the feet of Judas!

And so if we have ever felt the wrong |

Johnson Fears OldMusic Lost ForeverWax cylinders no longer playableW. Johnson, Editor In the late 19th and early 20th Century people like Dorothy Scarbourough and John and Ruby Lomax After interviewing hundreds of people, and recording hundreds more of their songs on wax and aluminium cylinders, and returning these to the Smithsonian Institution and other archives for storage, they believed their task had been accomplished. Not so. In the 1920s, Carl Sandburg began collecting songs on his travels, and writing them down. Carl Sandburg The music that he transcribed – and he was unable to transcribe all of it – was published in book form as The American Songbag and it is where I have found many songs that are only to be found on the Lomax cylinders, or on the 78s that Sandburg himself recorded. The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, Canned Heat, and the hundreds of other bands that started their careers by recording Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf and Willie Dixon songs, failed to find this treasure trove of folk and blues songs published in book form. Some of the songs collected by Scarbourough, Lomax, Sandburg et al are different versions than those that became standard blues tunes after being recorded by such artists as Leadbelly and Mississippi John Hurt: There is a version of “CC Rider” that I have found in Sandburg's book that not only has two other verses, but a written description of how it should be sung as mandated by the people who sang it for him. There is an alternate version of “The Ballad of Jesse James”, written from the point of view of someone sympathetic to his wife and family. These variations make for a more rounded interpretation of the type of songwriting that was going on in America in the late 1800‘s that is different from that which we have come to know today. The traditional folk songs Lomax, Sandburg, and others collected have many different forms, many different perspectives. There are other songs in these books, however, songs with emotional impact and poignancy, that I believe should be re-recorded and given a wider audience: “Levee Camp Moan” (recorded by Sandburg); “Hammerin' Steel”; “Dink's Song”; “Hopali” (recorded by Alan Lomax in the late 40's); and many others. To re-record and share these with as many people as possible has become my mission, and I will make every effort to record as many of these “unheard” songs as I can.  |

Black Poets Forgotten19th Century Poetry Charms JohnsonReading the works of Joel Chandler Harris, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and others, Johnson noticed similarities in the structure of some of their poems (repeating verses, refrains, and rhyme schemes), and concluded that these were actually written as songs – but without the music. Whistling Sam

I has hyeahd o’ people dancin’

In de kitchen er de stable,

When dey had revival meetin’

At de call fu’ colo’ed soldiers,

To de front he went an’ bravely

When de cruel wah was ovah |

But for some reason, the old time hymns aren't as popular. I think that one of the reasons for the demise of the these hymns is the fact that the words and language have been deemed archaic by those who decide which songs will be published and distributed to the churches.

But for some reason, the old time hymns aren't as popular. I think that one of the reasons for the demise of the these hymns is the fact that the words and language have been deemed archaic by those who decide which songs will be published and distributed to the churches.

began their search for songs and stories that told the story of America.

They traveled throughout the U.S. with recording equipment that was state of the art at the time, but was a far cry from the modern equipment we use today.

began their search for songs and stories that told the story of America.

They traveled throughout the U.S. with recording equipment that was state of the art at the time, but was a far cry from the modern equipment we use today.

He realized that many of these songs had been collected already (most notably by a colleague at Harvard University), but he was also aware there were different versions that he was getting from people he met on those travels. He began comparing his versions with those of the Lomax collection (some of the recordings being in a fragile state) and he began the arduous task of transcribing the music he himself collected, and some of the music on many of the more delicate cylinders so that it could be published. He also took the liberty of transcribing the music he found to be interesting to him, personally, and in order to preserve it, wrote his own arrangements and recorded these on 78 rpm records.

He realized that many of these songs had been collected already (most notably by a colleague at Harvard University), but he was also aware there were different versions that he was getting from people he met on those travels. He began comparing his versions with those of the Lomax collection (some of the recordings being in a fragile state) and he began the arduous task of transcribing the music he himself collected, and some of the music on many of the more delicate cylinders so that it could be published. He also took the liberty of transcribing the music he found to be interesting to him, personally, and in order to preserve it, wrote his own arrangements and recorded these on 78 rpm records.

Johnson began writing music for these based on late 19th century and early 20th century country blues melodies he learned from artists like Henry Thomas and Elizabeth Cotton. The choice of this type of music reflects what these songs may have sounded like were musical arrangements written for them by the original poets. Below is an example of one such poem: note the reference to a “tune“ or “melody” at the end of almost every line. I have written a melody that I will incorporate into the music I have composed for this song, an interpretation based on music that I think may have been popular during that era.

Johnson began writing music for these based on late 19th century and early 20th century country blues melodies he learned from artists like Henry Thomas and Elizabeth Cotton. The choice of this type of music reflects what these songs may have sounded like were musical arrangements written for them by the original poets. Below is an example of one such poem: note the reference to a “tune“ or “melody” at the end of almost every line. I have written a melody that I will incorporate into the music I have composed for this song, an interpretation based on music that I think may have been popular during that era.